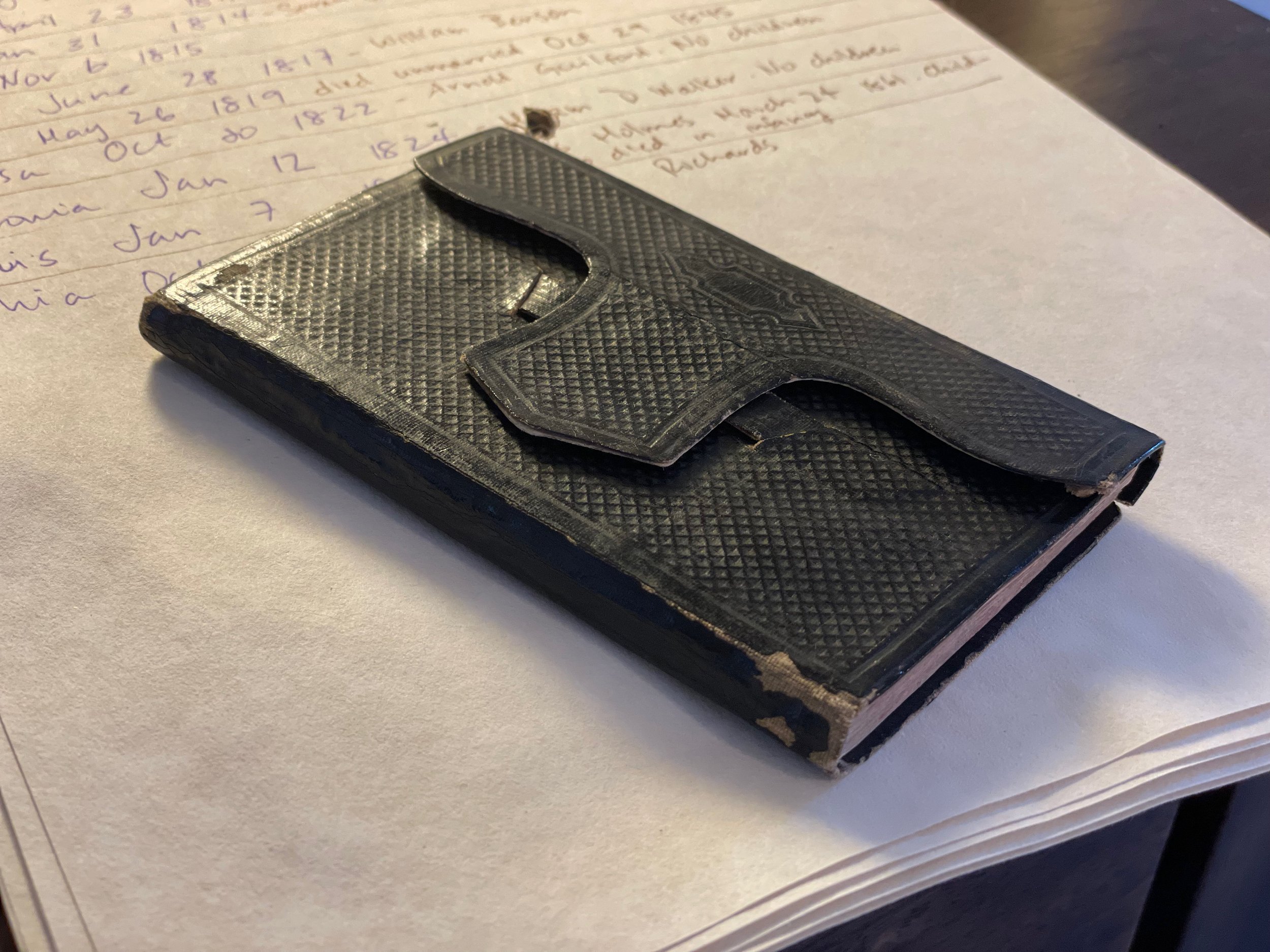

Sophronia Lumbard

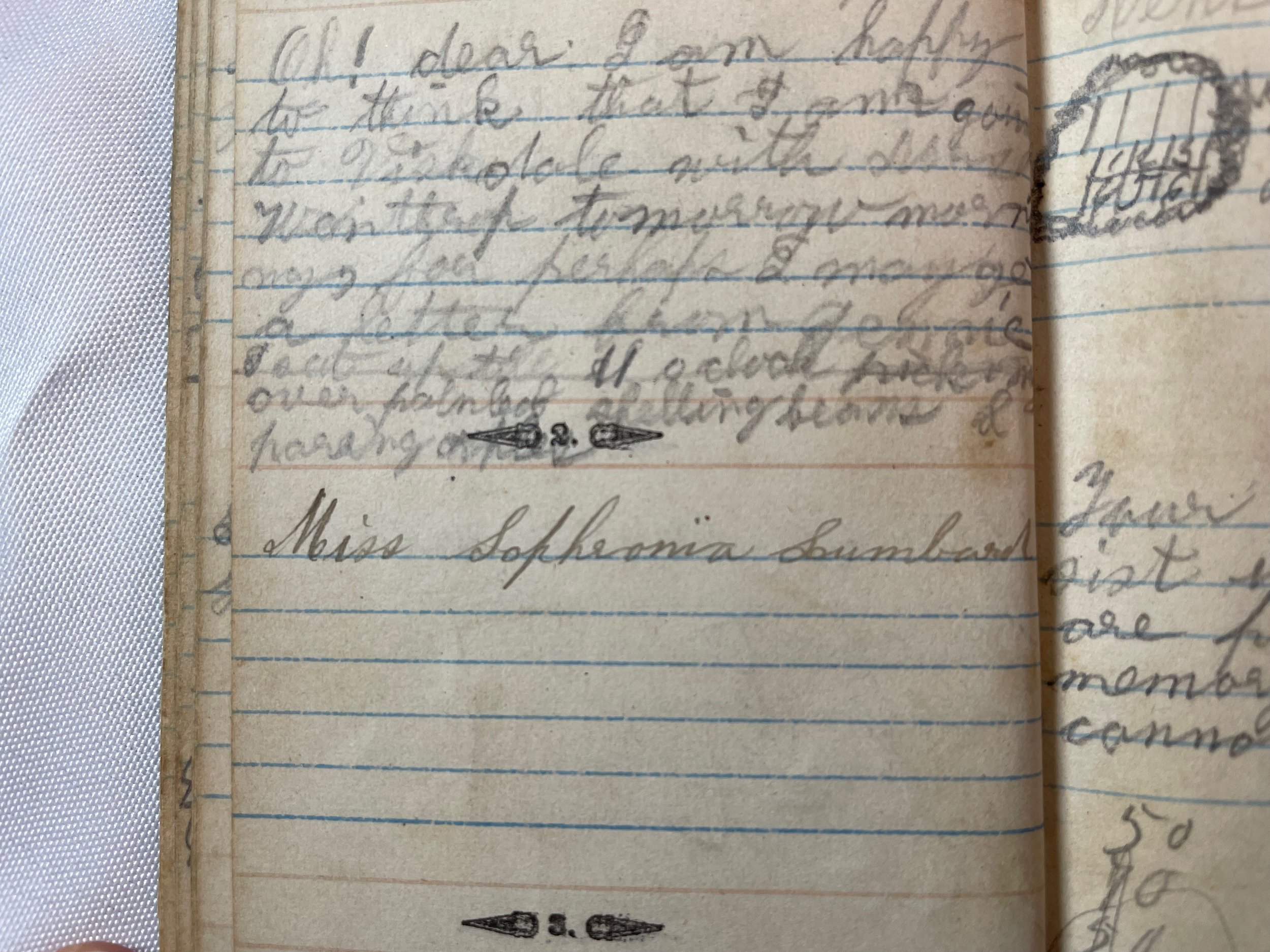

Miss Sophronia M Lumbard was born on March 29th, 1852, in Sturbridge, Massachusetts, and was 13-14 years old when she wrote her diary in 1866. Through the eyes of a young teenager, the time and town emerge around Sophronia.

1870 Plan of the towns of Sturbridge and Southbridge : from actual surveys and records. You can see the Lumbard’s, Hovey’s, Bemis’, Shumway’s, and Holmes’ farms clustered together near the Hampden County boarder.

Introduction

Sturbridge was colonized in 1729 and was officially incorporated in 1738. During that time, there were negotiations and conflicts with the Indigenous peoples of the place, the Algonquin-speaking Quaboags, and the growth of population and industry, including saw, grist, and cotton mills, lead and graphite mines, tanneries, and auger and shoe factories. There were hotels for stage coaches, trade shops, and the Town House in the Commons, up to 12 school districts by 1825, each with its own schoolhouse, churches and meetinghouses, and many dams to harness the river’s power. Still, much of the town remained agricultural, with the average farm being about 130 acres, and having horses, cows, sheep, corn, hay, and potatoes, crop land, wood land, and orchards.

Most communities were organized like this- a town center, with spoke-like dirt roads extending out and around geological features, with farmers populating the surrounding land. Most neighbors wouldn’t be more than a half mile from each other, creating little neighborhoods that would each perhaps have a school that would often serve other community interests in addition to schooling, a meetinghouse, a shop or two, and whose social life would also revolve around each other with the same families passing down farms for generations. The town of Southbridge broke off in 1811, depleting Sturbridge’s population and, therefore, its economy. Still, the town continued to grow and was at 2,291 inhabitants in 1860.

Massachusetts, U.S., State Census, 1865: You can see Aurea, Fannie, Sophronia, Nathaniel, and Betsey included

The diary opens on January 1st, 1866- a time of transition for a few reasons. As stated, the economy was changing from an agricultural one to an industrial one. By the late 1800’s farming was not generating the wealth that the mills were. Sophronia’s family and most of her friends’ families were farmers, but many worked in mills and making shoes, reflecting the times. Also, the diary begins just around 7 months after the end of the American Civil War. The generation most affected by the war is somewhere in between the major characters in her story, with her parents’ generation being a little too old to have fought and her generation being obviously too young. Still, some people in her life had gone off to war- her brother-in-law’s brother, Charles Upham, was a veteran, as well as a man in town that flirts with her teacher, Newton Wallace, and many of the other family-members-of-friends and friends-of-family-members that were in her life. In August 1862, the federal government required quotas of men from towns in the Union, and Sturbridge was required to enlist 43 men, including Nelson’s son, Franklin. All in all, 235 men from the town went to war, with 27 never returning.

Sophronia herself never mentions the war and, other than the inevitable loss of some of the men in town, perhaps it isn’t surprising that she wouldn’t mention it. Her parents were unaffected, after all, as well as her contemporaries. With her being in Massachusetts, she was miles and miles away from any of the fighting. As a young child, at home with her family, and her life mostly unaffected, it might not have meant much to her, despite the fact that she lived through it.

Really, she doesn’t mention much about life outside of her tight social circle. From the histories of the people she encounters, we can learn more about the vividness of life- their marriages, the deaths of children and spouses, the relationships that last lifetimes. Often, I might only know the years of people’s birth and death, the number of living children that they had, the towns they lived in, and their occupations. I love when I can find a will or a grave or military draft papers. Through these artifacts, we can get a glimpse of their stories. Because the people in Sophronia’s life were farmers and tradespeople, it is difficult to find them in history books or newspapers- they often led simple lives. Still, they were lives that were intricately intertwined with one another. The parents of the families were friends that helped on each other’s farms and hung out in the evenings. Their children all went to school together. Some children didn’t leave their parents until they died. Some spent their lives caring for children and grandchildren. Some married each other. Some even appeared in each other’s wills. These families survived together. It is these strong inter-family and intra-family ties that became clear through the genealogical work that I did in order to understand this small town and Sophronia’s place it in. I now know her family and the families around her well because, to understand her, I had to understand them.

Sophronia’s family features prominently in her diary, as you might expect for a young woman her age. Her father, Aurea (1805-1874) , was 61 during the writing of the diary and her mother, Fanny (Upham, 1815-1872), was 51. Obviously, her parents birthed Sophronia later in life than many parents of the time. Aurea was also born in Sturbridge and was one of nine children born to William (1774-1860) and Desire (Allen, 1773-1817), although one child died in infancy. Aurea was a farmer and they had at least horses, chickens, sheep, oxen, hay, beans, and potatoes on their farm. Fanny was one of eleven children born to William (1785-1872) and Dorothy (Dolly Winter) Upham (1815-1846). She kept house, along with Betsey and Sophronia’s help.

Speaking of Betsey… Sophronia was preceded by one sister, who was 24 years old at the time the diary was written. Betsey (1842-1880) had married Nathaniel Upham (1832-1907) on December 31st, 1863, when Sophronia was 11, and the two of them continued to live on the family farm in Sturbridge. Sophronia described taking care of her young nephew, Enos Nathaniel (1865-1954), in the diary when the adults would be attending meetings and funerals in the village. They also did errands and visited friends and family together. Betsey and Nathaniel would later have two more children, Erving William (1867-1940) and Fannie Belle (1871-1951).

She describes life on her family’s farm in her small village, mainly telling the events of her days and the people she visited. Indeed, not a day seems to go by where she doesn’t have multiple visitors and/or she doesn’t go visiting- Mr. Holmes, Mr. Winthrop, Mrs. Hovey, Uncle Nelson, Aunt Sophia and her children Arther and Bion, Grandmother and Grandfather, Lillie, Louisa, Albert, Charley, Georgie, Freeman, etc etc. She goes to school, skates on the pond in the winter, buys a valentine for Albert in February, hangs May baskets- again for Albert and also or Georgie, goes “huckleberrying” in late summer, plays cards with her father in the evenings, plays games with her friends after school, goes to “meeting” on Sundays, and travels to the surrounding towns with her father and brother-in-law to go to meetings, the schoolhouses, and to do errands for the farm.

The Diary

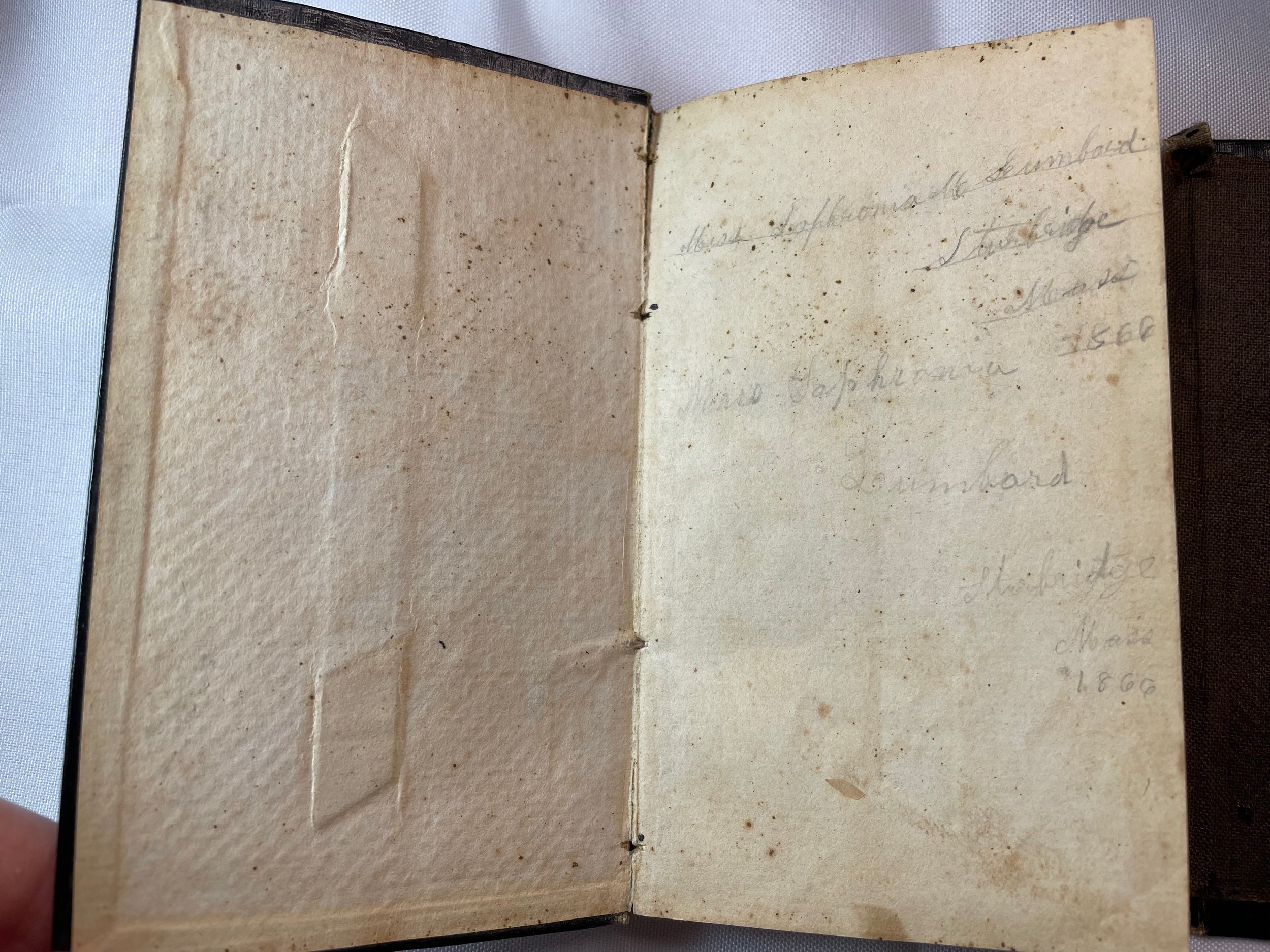

Sophronia begins her year in 1866 by signing, locating, and dating her diary’s inside cover in faded pencil. She does this twice on the same page.

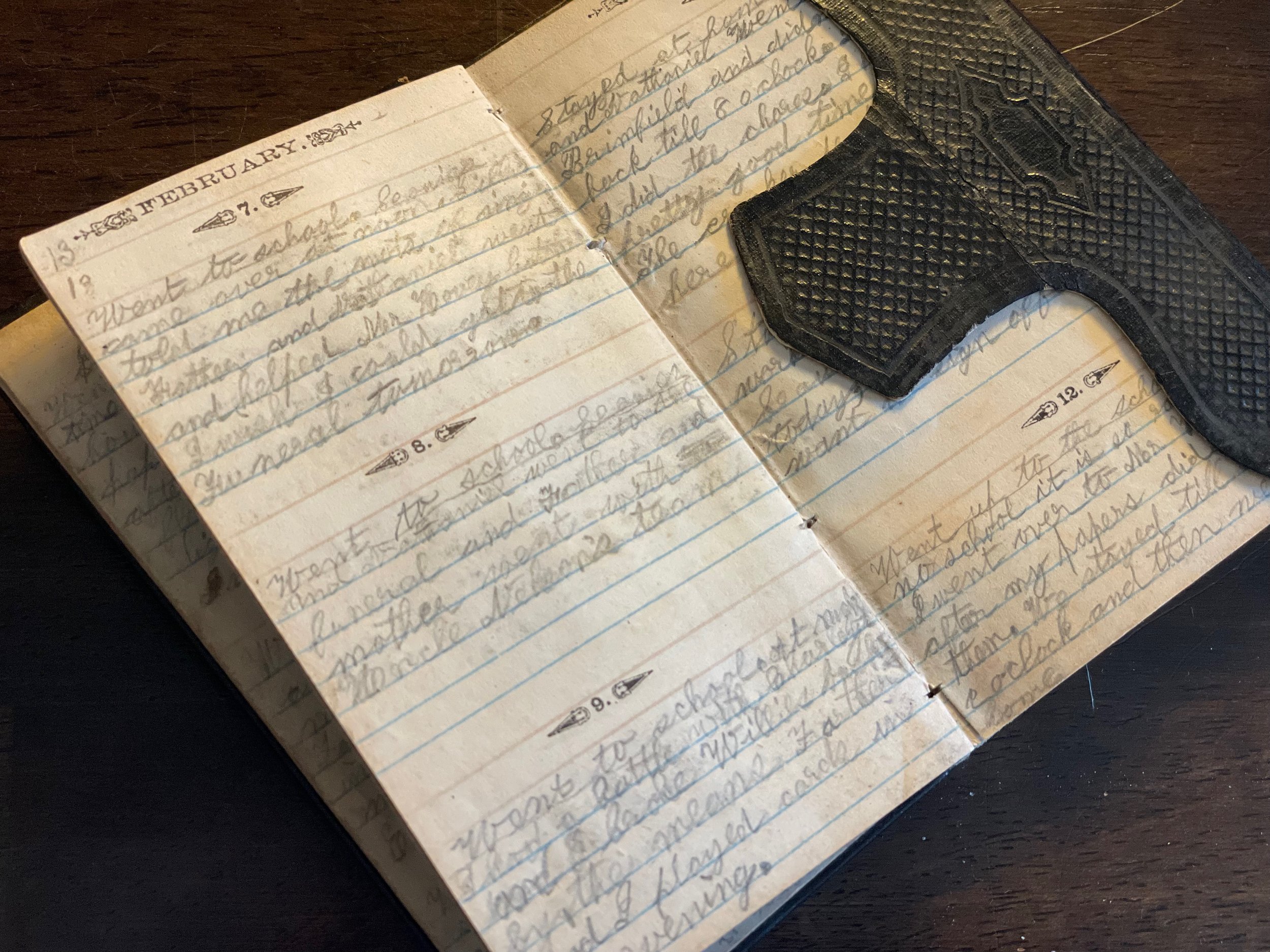

January might sound bleak in Massachusetts, but Sophronia is busy. Work on the farm is never ending and she goes to school, chats with friends about the New Year, and she helps clean the schoolhouse. A lot of her life revolves around the school- she enjoys her lessons and does a lot of socializing there.

January 4: Went to school and had a good time. Louisa came over to the school house and I subscribed for a paper. Lillie and i stayed after school and mopped the floor and came home by star light singing a piano tune.

January 31: Went to school had the darndest time at noon. The scholars made such a noise and thought I should be deaf drumming and pounding. We came home from school as if we was shot.

In early January, we also meet lots of people- her brother-in-law’s brother and his wife, Charles and Julia Upham; Newton Wallace, a Civil War veteran that is courting the school teacher; and Sophronia’s many friends including Lilla, Louisa, and Albert. The families in the neighborhood pass their evenings by visiting and playing cards together. I guess this is how farmers pass the winter months! Sophronia even stays on their farms overnight.

January 12: When I waked up in the morning Lillie had her arm around me. Ate my breakfast, and made Lillie bed, and then we started for school. Bill Culver was to our house today. Lewis Shumway came.

Church and religion are important for Sophronia and she talks about “her papers” and going to “meeting,” both of which I read as having religious connotations. She and her family even travel to other towns for meeting and to see children baptized. There were a few religions in Sturbridge at the time, including Methodist, Baptist, Quakers, and Universalists. I’m afraid that I don’t know enough about any of them to be able to recognize characteristics of them in the diary. She doesn’t discuss her own feelings about it much except when she reports not reading her bible when she was supposed to and this entry from February 23:

Went to school. Lillie got excused and I too. Georgie is sick. Lilie and I talked about religion. O if I was only prepared to die.

Gosh, sweet girl… so dark.

Early on, we begin to see that Fannie is both unwell and unpleasant with her family. Sophronia doesn’t complain, but she does describe. She doesn’t seem angry at Fannie, but it does seem that Fannie makes her life more difficult.

January 16: Went to school. Lillie said she almost fell in love with Georgie. Mother was not very well. I heated a brick and put to her feet. Father and I played cards in the evening.

January 21: Stayed at home of course. Mother was not very pleasant. I feel darn lame any way.

I’m not sure what is wrong with Fannie… she does die of heart-related issues not long after this, so perhaps it is physical illness. She could also be suffering from some mental illness as well, of course. Sophronia seems to have a good relationship with her father and never speaks poorly of him. I’m tempted to wonder if Fannie might be unhappy in her marriage, but there is no evidence for any of this.

Anyway, this is how Sophronia carries on… she skates at the pond and enjoys her school, friends, and family.

January 24: Grandmother went up to Uncle Nelson. In the evening Father came to my door and said that there was a lamb down to the barn. At noon we went out skating on the mud hole had a good time.

In early February, we see some of the harshness of the time. In the blink of an eye, the death of a child. Sophronia loses a small cousin, Clara Upham (1864-1866). She was the daughter of Lewis (1826-1892), who was Fannie’s brother, and Persis (Holmes, 1839-1868). Little Clara died of whooping cough on February 6th, 1866. Persis would die just over a year later on May 29th, 1867.

By February 13th, the excitement of Valentine's Day is upon Sophronia and her friends. She gets a Valentine for Albert Lamb, the son of a shoe maker in town. We also get small account as to who sent Valentines to whom. Very important! In fact, as the year goes on, she and Albert spend a bit of time together. Into March, they are seeing each other quite a few days a week.

I just love this entry; it shows such a fun, happy, but typical day for her. She even had to use more room on the next page to complete the entry.

March 30: I went up to Mr. Holmes and got my papers, and came back to Mr. Shumways and got my lamb, and then came home and did some work. Look to the next page.

March 31: I came home and helped Mother do her work and care of my lamb.

(Continuation from March 30, underneath March 31): And then I went up to Mr. Hoveys about three oclock and stayed all night. Had a pretty good time running out doors and hearing Lillie playing on the piano.

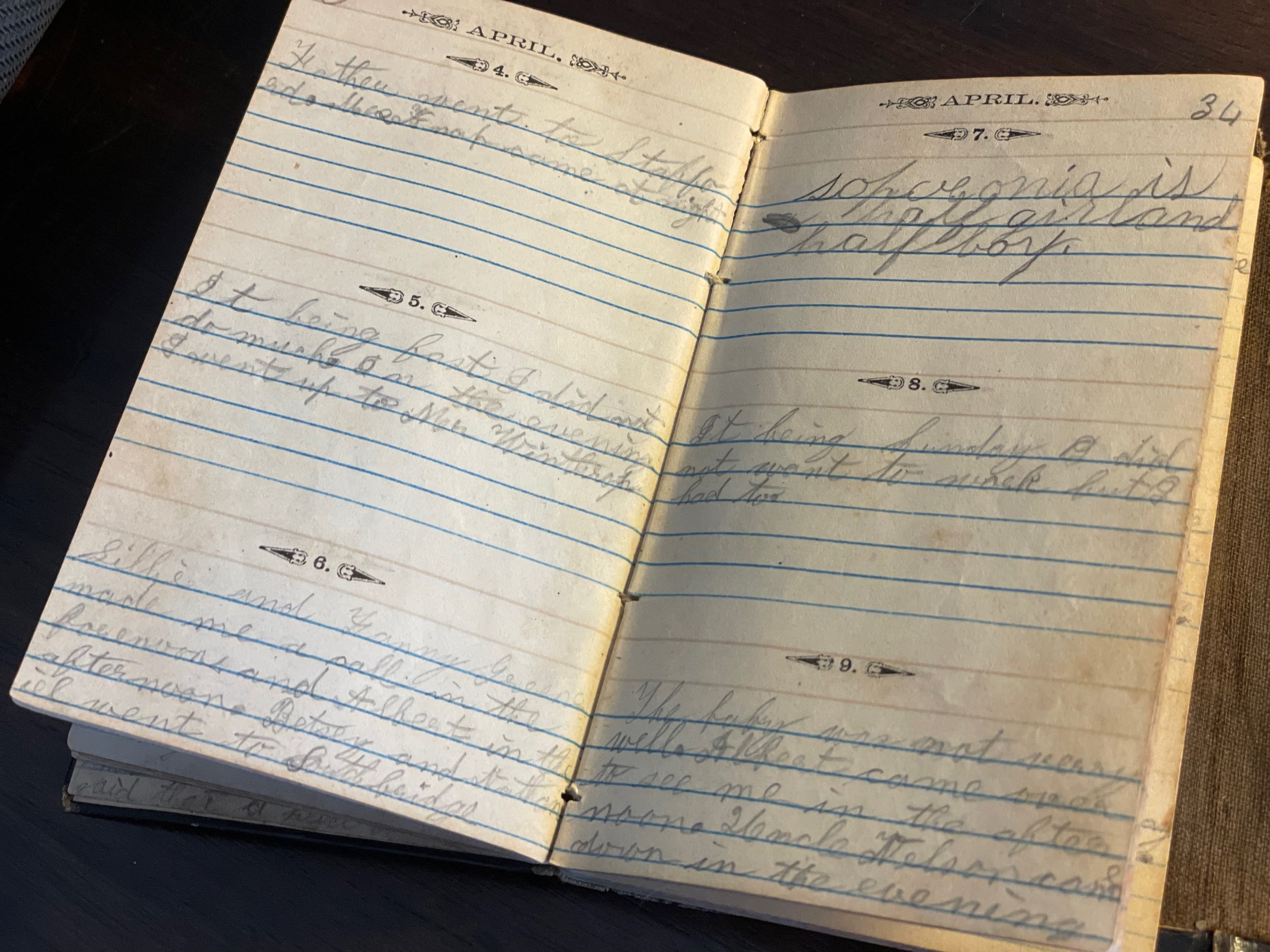

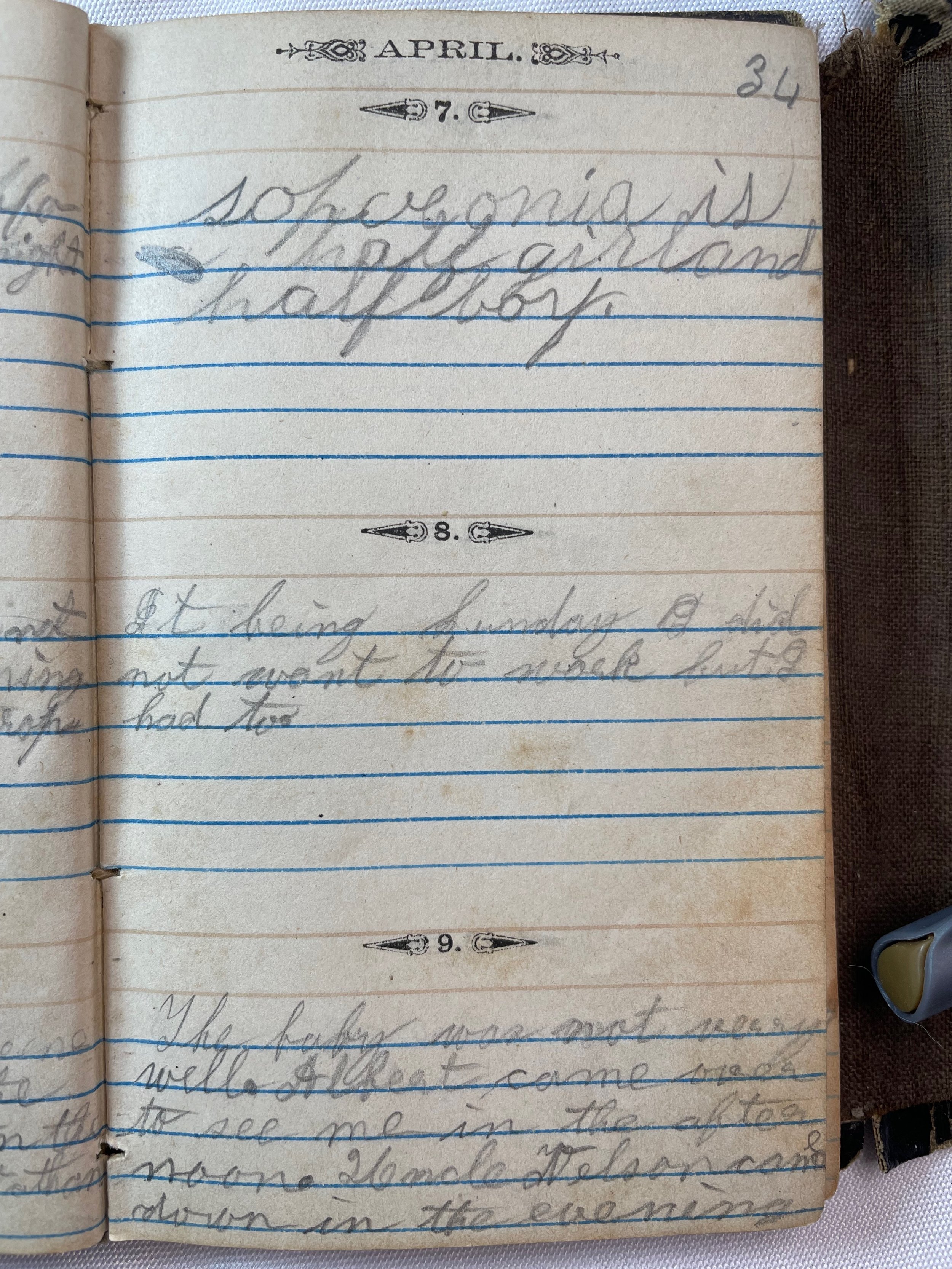

On April 7th, Sophronia includes a fascinating entry. She writes: Sophronia is half girl and half boy. See my thoughts about this below.

As May roles around, we get to see the tradition of the May basket!

May 2: In the evening I hung a May basket for Albert and George.

May 1st is half way between the spring equinox and the summer solstice, so it was celebrated! It was originally rooted in agriculture and has traditional roots in England. These traditions made their way to America with the colonists. Children would dance around the May pole, people would decorate with wild flowers, and make May baskets. These were often made of paper and people would fill them with flowers and treats to leave on the doorsteps of the person you had a crush on. It was supposed to be done in secret. Sophronia gives one to both George and Albert, who both later figure out that it was her. In fact, George asks her on May 10th whether she also gave one to Albert… sounds like George had his feelings hurt a bit.

May also brings about the beginning of the planting season and Sophronia works hard on the farm almost everyday planting potatoes and corn. Summer is also a time for visiting and travel. Sophronia and her family- mainly her father, Betsey, and Nathaneil- visit their friends and travel to other towns for meeting and farm chores. Her Aunt Sophia and Sophia’s two sons, Arthur and Bion, also come to visit the Lumbards.

July 1: I went to meeting over to Holland to the center schoolhouse. I rose for prayers. Mr. Jackson was the preacher. I then went over to the meetinghouse. And heard the afternoon services, and then went to Mrs. Webbers and stayed till 5 oclock and then went to the schoolhouse to meeting, and then Freeman and I came home. A happy day spent.

As time goes on, Sophronia isn’t as descriptive in her diary. During the late summer and early fall, her entries are still substantive, but they are getting shorter. She talks about who visited, as always. She describes a joke that she played on Freeman Webber. She writes things like, “Not much to speak of,” or “Ditto,” in many of the entries as the diary goes on. Then, she starts to get less descriptive and to use the diary to jot things down- little saying that she wants to remember and she writes her name in pen, as opposed to the usual pencil that the diary is written in, a few times. She does start school again in early September and is happy to be back.

September 28: Love every one and treat them well and you will have no trouble

October 5: Your happiness will consist in doing good. They are pleasing spots in the memory which vexation cannot erase

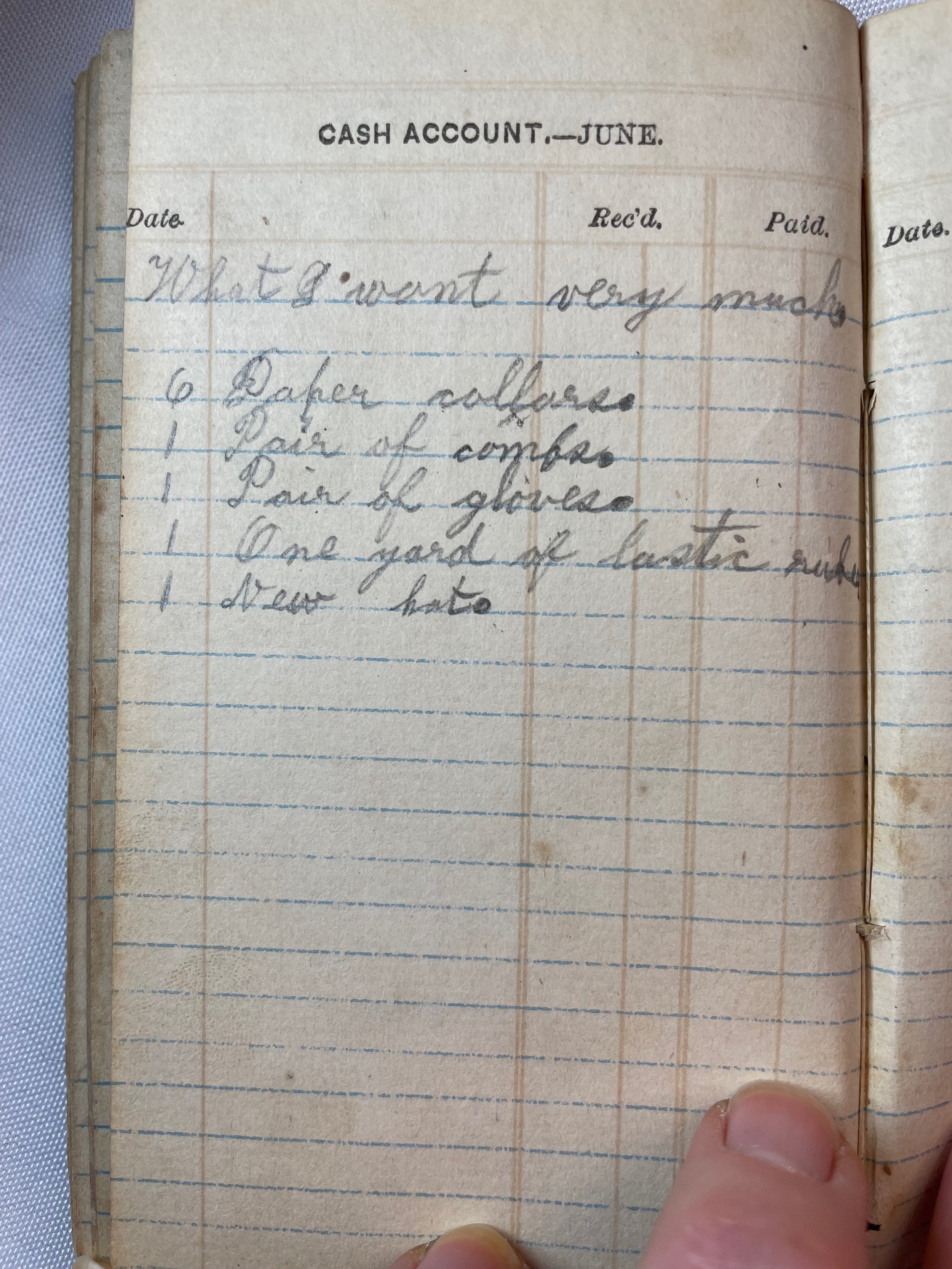

The above is the last real entry. Then, she uses the space under October 6th to count hens and eggs. Then, she’s silent. At the very end, on a page meant for keeping track of expenses, she writes:

What I want very much.

6 Paper collars.

1 Pair of combs.

1 Pair of gloves.

1 One yard of lastic ruber

1 New hat.

After

I have evidence of Sophronia in Sturbridge in 1855, 1860, 1865, 1866, and in 1870 at the age of 18 from Massachusetts State Censuses, the US Federal Censuses, and the diary. Then, I lose track of her for 10 years. During this time, Sophronia suffers a list of losses. Her mother, Fanny, died of heart disease at the age of 56 in 1872; her father, Aurea, died at the age of 68 in 1874; and her sister, Betsey, who had moved 7 miles away to a town called Brimfield sometime between the birth of Erving in 1867 and the 1870 Census, died on March 27th, 1880, at the young age of 37 from complications with her heart. These deaths occurred for Sophronia when she was 20, 22, and 27 respectively.

Then, at 28 years old in 1880, Sophronia turns up in Southbridge, a town just 3.5 miles from Sturbridge. She is now a housekeeper in the home of Henry N. Vinton (1832-1915), a spectacle manufacturer. She lives there with Henry’s wife, Mary E. (Wilson, 1845-1912), their daughter Lula A. (1873-) who is 7 years old at the time, and a divorced or widowed (depending on the source) boarder named Meruck Bracket who assists Henry in the spectacle shop. This is the first evidence that Sophronia has left home and, importantly, is earning a wage.

As if losing Sophronia for 10 years wasn’t difficult enough, I now lose her for 20 years. It would turn out that almost 99% of the US Federal Census from 1890 would be lost in a fire. In 1900, Sophronia turns up in Millbury, almost 21 miles from where she grew up in Sturbridge. She is still a housekeeper, but now in the home of Herbert W. Nutting (1845-1915), his wife Carolyn E. (Lombard, 1852-1891), and their three children, Earle A. (1882-1963), Ralph L. (1885-1968), and Nellie S. (1887-1947). Herbert is a carpenter. Carolyn (“Carrie”) is his second wife; he lost his first wife Ellan (1848-1879) after 9 years of marriage. In 1880, he married Carolyn in Millbury and they had their children, but this marriage will only last for nine years as well. Carolyn died in 1891 at the age of 39, just four years after Nellie was born.

Why did Sophronia make the choices she made? Her diary tells of a girl who was independent, hardworking, and loved school. She enjoyed work and rarely complained about school or chores on the farm. For example, she often stayed late after school to help clean and she often expressed the most happiness after doing hard chores. She even said on March 15th, “O dear I wish I was out to work earning something,” after a particularly difficult day with her mother, “Mother is not very pleasant today.” I think this entry, when she pairs her desire to earn her own living with her observations of her mother, is telling.

Sophronia only expressed negative feelings a few times in the diary, but about half of those times were about her mother. She grew up with a mother that was sickly and unhappy, but she was surrounded by industrious men that would involve her often with their work running the farm. She was the only child there after Betsey left, so she, her father, and her brother-in-law, along with other hired hands at times, were the ones running the farm. I think that her independence and early years with her family made her want for a different life than her sister and mother had.

On April 7th, for example, Sophronia’s entire entry reads, “Sophronia is half girl and half boy.” When thinking about the possible meanings for this entry, I have come up with a few, particularly in light of Sophronia’s future choices. Could she have been grappling with her sexuality? I suppose this is possible with the data I have, but she does has crushes on boys and even acts on those crushes. Of course, she could identify anywhere along the sexual orientation spectrum and perform having crushes on boys, particularly given the expectations of the time. I don’t have data that contradicts this possibility, but actually, after getting to know her and thinking about her life and writing, I think that that isn’t the right direction to go for an explanation for both this entry and her future choices. I think that this is the only language that a 14 year old girl in the year 1866 has to express her conflicted feelings about the expectations placed on her. Yes, she enjoys her girlfriends, caring for her young nephew, and probably many other traditionally female things, but she also enjoys work, being productive, and being independent. That, coupled with an unhappy mother, makes her yearn to break the mold of womanhood, earn a wage, and escape.

Haven’t we all felt this way? That our inner selves aren’t perfectly conforming to how we ought to act, who we ought to be? I certainly have. Now, as was the case then, women are pressured to marry and have children, as if we owe that to society. If a woman doesn’t do these things, the tendency is to ask why and the language can quickly turn accusatory and incorporate other socio-cultural power and privilege connotations- What’s wrong with her? Why is she not motherly?

I have felt this pressure throughout my life OF COURSE. I, like Sophronia, always wanted to work, earn a wage, make enough money to take care of myself. Some of this was driven by anxiety, I think. I have always wanted to be able to take care of myself in case I ever needed to for my own survival, always feeling like I had to hustle at full speed lest the world swallow me up. My method for doing this was to get a bunch of degrees- things that couldn’t be taken from me and would always be valued. I have gotten married and share the burden of existing (financial, emotional, etc.) with my husband, but I have never wanted children. There are many reasons for that, including the anxiety of existence- what if I lose my job and need to live under a bridge? What if climate change decimates wildlife and the environment and I have sentenced an innocent to live in that world? I mean, fuck, Donald Trump was president! Also, though, I’m kinda too selfish for children. I like having my life and my priorities. When envisioning the future that I wanted for myself, children were never part of the picture.

I think I’m lucky that I didn’t grow up in a family or ideology that was particularly set on me having children, but the world still expects it of me. I have also internalized a lot of that rhetoric myself; I observed that when I was thinking about why Sophronia made the choices that she did. I asked the same questions of her that I’m sure others have asked of me. Ultimately, I think we both just had other ideas for our lives.

At the time that Sophronia left home, rural life was changing. Farms in New England were increasingly requiring outside income to sustain them, and farmers were supplementing their income by doing things like buying shares in mills, learning new part-time trades, or selling more of their farm-grown products. With the increase in railroad transportation, goods could be shipped further, increasing the demand for large-scale manufacturing. Farms were no longer able to support large families and generations of sons. Indeed, in Sophronia’s parents’ generation, sibling groups might be 8, 10, or 12 children, but by Sophronia’s generation, sibling groups had shrunk to 2, 4, or 6 children as parents made different decisions about their families. Many farmers that were still interested in that way of life worked on other families’ farms as farm hands (like Nathaniel and his sons) or were beginning to move west, to the Midwest- Ohio, Illinois, Iowa- and eventually beyond (like the Shumways, Harriet Chickering, and others). Her generation was the first that might be born on a farm, but was less likely to die on one. After the Industrial Revolution, there was work for women outside their homes. Indeed, women worked in cotton mills and made shoes, they made straw hats and caned chairs, they painted tinware and clock faces.

When her father died, Sophronia was young, only 22. She could have made a few choices- she could have gotten married, she could have moved to a family or friends’ farm to help in their homes, or she could have made the choice that she did- to leave home and make her own way in the world. As far as I could tell from the diary and from learning more about her town and family, she didn’t have any examples in her life of women that didn’t marry and have children, that chose to make their own living. Arguably, this was the scarier choice for Sophronia, but there she was in the historical record, far from home, in a house that was not her own, creating a different life, one where she continued to be independent and to earn a wage like she had wanted to as a child. As a housekeeper, her work came with room and board as well as a wage. It implied that Sophronia would live in the house of her employer, so she would have all her needs taken care of and not have to live at home, on her own, or ever get married.

The connections she made in this different life were, I’m sure, not less meaningful, as I found evidence for…

The Nutting family becomes important to Sophronia, who as you can tell by now, never married or had children. Indeed, she stays with this family for the rest of her life earning her living as a housekeeper. She stays with them after the death of Carolyn, and can be found in 1900, 1910, and the Millbury City Directories from 1902, 1905, and 1917 still living with the Nuttings. Herbert died in 1915 at the age of 69, but Sophronia can be found in the home of “E A Nutting”- the eldest son, Earle- in the Millbury City Directory in 1917. I don’t know exactly when Sophronia began working for the Nuttings- she was there for at least two decades, from at least 1900 until her death in 1919-, but I think she was there even longer.

You see, Sophronia inherited her name from an aunt- Fannie’s sister, who was nine years her junior. Aunt Sophronia’s husband, Hiram Walker, would bring Sophronia oranges as a treat back in 1866. With four sisters to choose from (Lydia, Clarissa, Sophronia, and Sophia), I like to think that Fanny and her sister Sophronia were particularly loving, especially since Fanny seemingly became unhappy in her later life. Perhaps most telling about Sophronia’s relationship with the Nutting family and the life that she built with them is the fact that Herbert and Carolyn named their third child and only daughter Nellie Sophronia Nutting in 1887. In 1890, only 15 girls were given Sophronia as their first name, so it was very uncommon. The likelihood that this was not in honor of their housekeeper is tiny. This gesture- the giving of a servant’s name as a precious daughter’s middle name- in my opinion, speaks volumes as to the relationships that Sophronia built in that house and fills my heart for Sophronia. I hope it filled hers too.

Sophronia died in Millbury in 1919. I don’t know how, but I hope she was in Earle Nutting’s home, with his wife, Annie, and their son, Elmer, who had been born just the year before.